Hokkaido University researchers have found a soft and wet material that can memorize, retrieve, and forget information, much like the human brain. They report their findings in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The human brain learns things, but tends to forget them when the information is no longer important. Recreating this dynamic memory process in manmade materials has been a challenge. Hokkaido University researchers now report a hydrogel that mimics the dynamic memory function of the brain: encoding information that fades with time depending on the memory intensity.

Hydrogels are flexible materials comprised of a large percentage of water — in this case about 45% — along with other chemicals that provide a scaffold-like structure to contain the water. Professor Jian Ping Gong, Assistant Professor Kunpeng Cui, and their students and colleagues in Hokkaido University’s Institute for Chemical Reaction Design and Discovery (WPI-ICReDD) are seeking to develop hydrogels that can serve biological functions.

“Hydrogels are excellent candidates to mimic biological functions because they are soft and wet like human tissues,” says Gong. “We are excited to demonstrate how hydrogels can mimic some of the memory functions of brain tissue.”

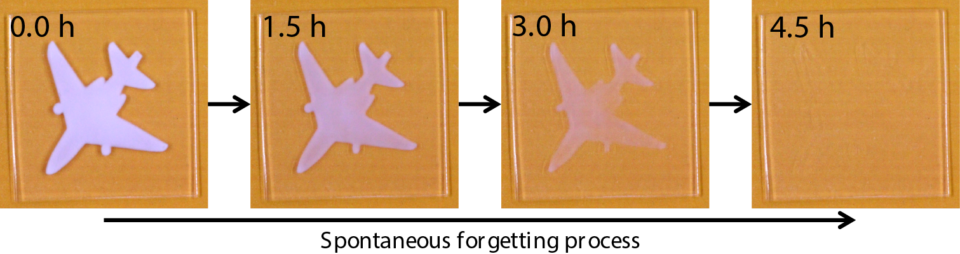

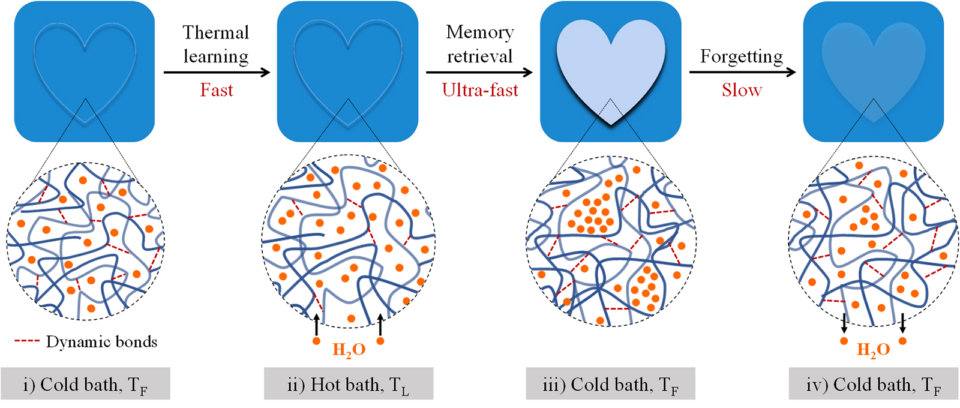

In this study, the researchers placed a thin hydrogel between two plastic plates; the top plate had a shape or letters cut out, leaving only that area of the hydrogel exposed. For example, patterns included an airplane and the word “GEL.” They initially placed the gel in a cold water bath to establish equilibrium. Then they moved the gel to a hot bath. The gel absorbed water into its structure causing a swell, but only in the exposed area. This imprinted the pattern, which is like a piece of information, onto the gel. When the gel was moved back to the cold water bath, the exposed area turned opaque, making the stored information visible, due to what they call “structure frustration.” At the cold temperature, the hydrogel gradually shrank, releasing the water it had absorbed. The pattern slowly faded. The longer the gel was left in the hot water, the darker or more intense the imprint would be, and therefore the longer it took to fade or “forget” the information. The team also showed hotter temperatures intensified the memories.

“This is similar to humans,” says Cui. “The longer you spend learning something or the stronger the emotional stimuli, the longer it takes to forget it.”

The team showed that the memory established in the hydrogel is stable against temperature fluctuation and large physical stretching. More interestingly, the forgetting processes can be programmed by tuning the thermal learning time or temperature. For example, when they applied different learning times to each letter of “GEL,” the letters disappeared sequentially.

The team used a hydrogel containing materials called polyampholytes or PA gels. The memorizing-forgetting behavior is achieved based on fast water uptake and slow water release, which is enabled by dynamic bonds in the hydrogels. “This approach should work for a variety of hydrogels with physical bonds,” says Gong.

“The hydrogel’s brain-like memory system could be explored for some applications, such as disappearing messages for security,” Cui added.

Original article

Chengtao Yu et al., Hydrogels as Dynamic Memory with Forgetting Ability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), July 27, 2020.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2006842117

Funding

This study was supported by The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (JP17H06144, JP17H06376, JP19K23617).

Contacts

Professor Jian Ping Gong

Institute for Chemical Reaction Design and Discovery (ICReDD)

Graduate School of Life Science

Faculty of Advanced Life Science

Global Station for Soft Matter (GI-CoRE)

Hokkaido University

Email: gong[at]sci.hokudai.ac.jp

Naoki Namba (Media Officer)

Institute for International Collaboration

Hokkaido University

Tel: +81-11-706-2185

Email: en-press[at]general.hokudai.ac.jp